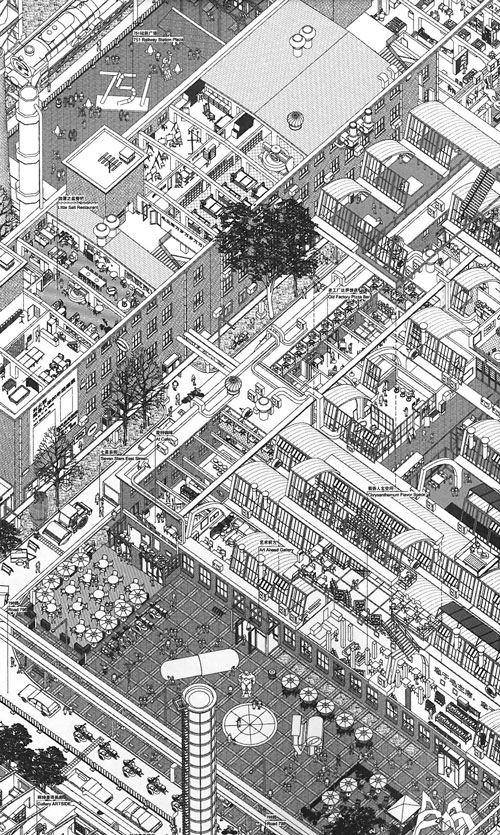

The Winterslag coal mine in the city of Genk (Flemish Limburg region) has begun a new life as a centre of culture and creative industries. At first, temporary events were organized in the abandoned mining complex, to increase the relationship with the city dwellers and counter the decay of the buildings. In 2005 the first new tenant arrived – Cinema Euroscoop. The new liveliness paved the way for other programmes, such as the Media and Design Academy and young creative enterprises. C-mine is slowly becoming the cultural hub of Genk.

Local market in the engine room of C-mine

Nowadays, C-mine is also a tourist attraction, featuring tours through various parts of the mine, as well as cultural events and gastronomy. The renovation design, by NU Architectuuratelier, focuses on the visitor’s experience and provides contemporary facilities for the creative functions. The design is rather clean compared to the coal mine compex Zeche Zollverein, near Essen, Germany (masterplan by OMA). The latter is a much larger complex, which is partly left in its original state to decay.

The entrance to the mine shaft, with on one side the White Tunnel (where clean workers went in) and on the other the Black Tunnel (where dirty workers came out).

Air pump that supplied the mine with fresh air

Underground artist installation – simulating the speed of a mine gas explosion

The bigger picture

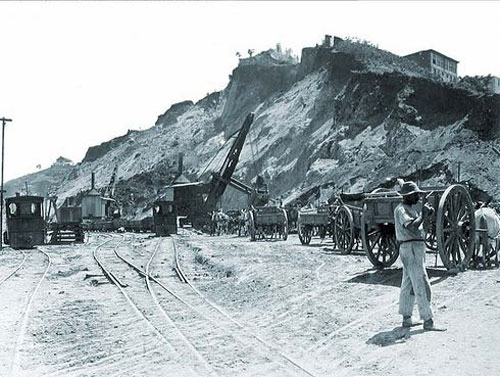

The Winterslag mine is part of an entire mining region, where it used to provide employment to thousands. The mines are still very recognizable in the landscape – as elevator towers and strange mountains of rubble. They are also still a crucial part of the regional history and culture, since many young people have a father or grandfather who used to work in the mines. These stories frequently come back in the C-mine exhibition.

Another coal mine, seen from the C-mine main elevator tower

Rubble ‘mountains’ of nearby mining areas