January 2014, German chancellor Angela Merkel is publicly not-amused by the news that her cell phone is being monitored by the NSA. The United States and the European countries are in a crisis of confidence. I am in Berlin, about to visit a notorious Cold War relic: the NSA “Abhörgelände” (spying station) on top of the Teufelsberg.

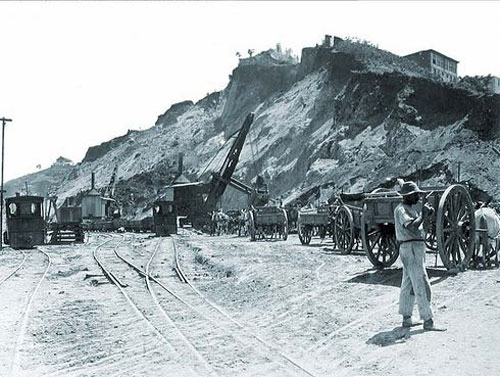

From S-bahn stop Grunewald it’s a 20 minute walk through the forest. The area, distant from Berlin’s core, was already pointed out as a good site for a meteorological faculty by the nazis. Things developed differently though. In the early 1960’s, the part of Berlin occupied by the allied forces became a walled island within the DDR. Millions of tons of rubble from the war period still had to be carried out of the city. As West-Berlin was a very limited territory, the rubble was piled up in the parks. The Teufelsberg (Devil’s hill) is the highest of Berlin’s rubble hills, 120 meters high. In the 1950’s the intention was to shape the hills into a ski slope (part of the area actually has this function). The Cold War, however, made the area into a tactical outpost for the Americans to spy on the Russians and the countries of the Warsaw Pact.

Few years after the unification of Germany, in the early 1990’s, the complex was sold to a project developer, who wants to build a luxury residential and leisure resort. Until today, the plans have been unsuccesfull because the investments are quite high and the housing units would under the current circumstances be too expensive. In the meantime, squatters have broken in to the complex several times and have destroyed some of the buildings and facade materials. At this moment, an independent association leases the area in order to organize guided tours and grafitti festivals, while protecting the structures from further depredation. I joined one of the two-hour historic storytelling tours. In my group one guy appeared with his drone, to actually film the old NSA spying towers from above – is this the world turned upside-down or what?

Besides the technical and historical information, juicy details were also supplied by the tour guide. For example, that about 7 years ago film director David Lynch tried to buy the premises to turn it into a University for Floating (a meditation technique developed by the Indian guru Yogi in the 1950’s). The plans didn’t go ahead.

Art work inside the main dome of the spying station.

Despite the clear importance to maintain the complex as a Cold War relic for future generations, the strategy of the organization doesn’t totally convince yet. They disapprove of any type of private use and investment, all use should be public (art galleries and studios for example) and all investments should hence come from the tax payers. Just straightforward Berliner activism perhaps, something we’re not used to anymore in the all too pragmatic lowlands. So for the time being things remain temporary and mysterious, also very much in the spirit of Berlin.

View towards Berlin through the tower facade of the spying station, ripped open by squatters.