This week we presented SprintCity, a project by the Deltametropolis Association in cooperation with TUDelft and Movares, at the BUFTOD conference in Paris (Marne-la-Vallée). SprintCity investigates opportunities for transit-oriented development (TOD) in The Netherlands, using a simulation game toolkit based on real data, with the real stakeholders. Besides sharing results of this project so far with urban planners, the goal of the presentation was to discuss whether this planning support tool can be effectively implemented in other regions and city’s. Fortunately, the international community gave a very good response to the project and suggested fruitful applications in the city regions of Toulouse, Paris, Bogotá, Alicante and the central plain of Mexico. Hopefully, a couple of these applications can actually happen over the next year. Click here to download the SprintCity folder (English).

The BUFTOD 2012 conference joined several international researchers and planners. There was a certain Eurocentric perspective, followed by North America and Asia. Although some of the efforts were ‘lost in translation’, in general it was a good opportunity to build a TOD network. The Dutch were extremely well represented, with several universities and case studies. I took a Thalys train with Dutch researchers from the University of Amsterdam and Delft University of Technology.

Dutch TOD specialists on their way to Paris

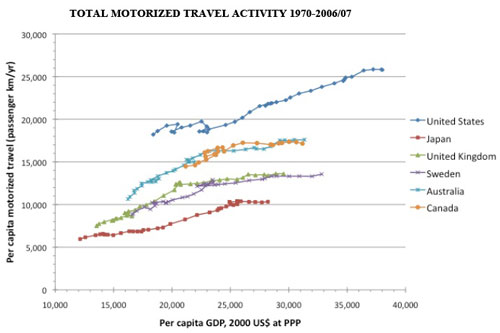

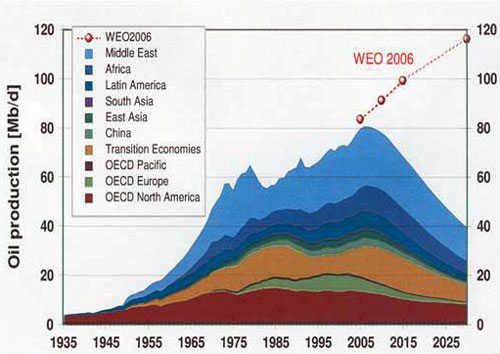

International good practices were compared, contributing to better understanding of different development models and the specific conditions that led to these strategies in each country. It became clear once again, that ready-made solutions (prêt-a-porter) don’t exist. However, we can learn of how each case has managed to remove a barrier to TOD. A few notes:

Robert Cervero, a known authority in the field of TOD, mentioned the importance of organized density (Curitiba) in contrast to scattered density (São Paulo); the potential of functional mix and re-use of brown-field sites and industrial complexes near transit stations (Dallas, Seattle); and high integration of Bus Rapid Transit systems with surrounding development (Guangzhou) versus low integration (Bogotá). Cervero was rather surprised with the critical Dutch projects at the conference, since the Dutch slow traffic and public transport systems generally serve as good examples abroad.

Claude Soulas showed the Port-Vert project in Noisy (Marne-la-Vallée), about inter-modality around the regional RER train system. Currently, the bicycle feeds 1,8% of these metropolitan trains, whereas the best European practices reach 40-50% of bike pre-transport to railway stations. Furthermore, the functional mix of greater Paris needs to be improved, as the East is predominantly residential and the opposite side around La Défense concentrates a huge amount of jobs.

Rental bikes, in front of the Notre Dame cathedral

Adrien Gey presented a circular slow traffic network in the Grand Paris region, connecting various parks and natural sites to housing and work areas. Guowen Dai demonstrated some of the challenges around the new high-speed South Station in Nanjing. An area of 32 square kilometers should become a ‘new town’ of 60.000 people. However, current urbanization has not occured according to the master plan, and integration of the station with metro and road networks will be challenging. Wendy Tan showed that TOD projects all over the world keep track of each other and sometimes copy-paste design solutions from other contexts into their own.

Maria Palumbo analyzed the motor-taxi system in Cotonou (Benin), which is starting to evolve into a formal system by recognizable yellow driver t-shirts. The Cotonou model is being exported to other cities in the West-African region, such as Bamako in Mali. Armando Padilla investigated TOD implementation possibilities in the Alicante province and Murcia region, according to the Dutch Stedenbaan experience. The polycentric region suffers from sprawl and the real estate crisis, which makes improvement of rail transport very challenging.

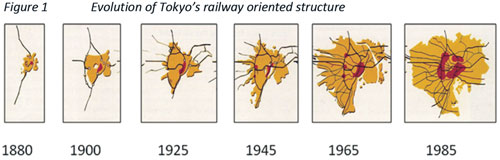

Juliette Maulat presented metropolitan density targets for a rail corridor west of Toulouse. Between 2000 and 2010 the frequency of the service was raised to 4 trains per hour, leading to an increase in ridership. However, the improvements on the transport system merely supported urban development, and did not shape them to the desired densities. Paul Chorus demonstrated that the Tokyo metropolitan government regulates density and public space around transit stations by granting higher floor area ratios to developers. Transit companies develop diverse activities along a corridor to create off-peak travel and make more profit. The companies gain life-time concessions and thoroughly investigate their territory and residents to optimize revenues.

Elina Krasilnikova and Yulia Ivanitskaya presented the longitudinal industrial city of Volgograd (Stalingrad), with 100km length and 9km width one of the longest cities in the world. A new waterfront transport axis could initiate redevelopment of the industrial sites along the river and make place for a linear park and leisure facilities. Wulfhorst and Alain L’Hostis discussed the German-French collaboration project Bahn.Ville, which was directed at integration of transport and spatial planning at two reference sites: St. Etienne and Thaunusbahn (Frankfurt). Implementation of TOD in Saarterassen, near the French-German border, is still difficult due to sectoral responsibilities and lack of an integrated lobby agent for TOD. Despite these setbacks, they have the following advice: ‘Don’t Wait! The time is now, the place is here! Start testing implementation of TOD right away.’

Photograph of Volgograd, taken from the International Space Station

Read more:

SprintCity planning support tool in Utrecht

Atlanta BeltLine – lecture, debate and booklet

SprintCity – spring 2011

Hong Kong public transport nodes

SprintCity goes China